Bacterial Speed Limit

Physics constrains bacterial investment strategies

Microorganisms, like all living beings, must perform multiple tasks on a limited budget. To succeed, it is essential to invest wisely and balance risk and reward. For bacteria, motility plays a pivotal role in environment colonization and infection, yet it is particularly resource demanding. So how do they decide how much to invest? Researchers led by Victor Sourjik at the Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology in Marburg have discovered that investments in motility are ultimately limited by the physics of swimming. This finding could help us better understand how bacterial strains adapt to diverse environments, including the human and animal gut.

Proteins are the primary currency in the cellular budget, as they perform almost all cellular functions. Since the environment can change constantly, microorganisms must dynamically adjust their protein composition to redistribute resources across competing needs. Researchers under the leadership of Victor Sourjik have set out to uncover the mechanisms that govern this fine balance across different environmental conditions.

One of the most expensive functions in microorganisms is motility. Motile bacteria swim by rotating long, helical flagella that are powered by molecular motors. Multiple flagella form a bundle, which, like the helices of a boat, propels the bacterium in the liquid environment.

Motility helps bacteria to colonize various environments but it can consume up to 8% of cell’s protein budget, primarily for the construction of flagella. This leads to a clear trade-off between growth and motility. While previous studies have mainly investigated the investment in motility in relation to growth, the factors that determine its upper limit remained unclear.

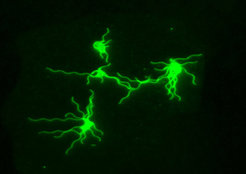

The researchers genetically modified the Escherichia coli bacterium and made it invest in motility more or less than the native regulation allows. It turned out that, while cells could produce more flagella than under natural regulation, the ability to increase swimming speed by adding more flagella remained limited. "We wondered, therefore, on which level the limitation occurs. Fluorescence microscopy analysis of the stained flagella showed that there is no cellular bottleneck: the bacteria can indeed produce more flagella that are fully functional," says Irina Lisevich, first author of the study.

To answer this question, the researchers developed a comprehensive mathematical model of bacterial movement that included numerous parameters of the flagellum and the cell body. This model reproduced the same saturation of swimming speed as observed experimentally. "As soon as the number of flagella per cell exceeds that of the wild type E.coli strain, which is four to five flagella, the bacterium does not swim faster, because the increase in viscous friction due to the additional flagella offsets the additional propulsion thrust they provide. Thus,overexpressing flagellar genes does not offer the bacteria any additional benefit, but only higher fitness costs," says Remy Colin, the second author of the study who developed the model.

"This is, to our knowledge, the clearest example of how physics constrains the physiology and evolution of gene regulation in microorganisms," says Victor Sourjik. “The topic of 'bacterial economics' has received a lot of attention in recent years. Our work shows that we must take into account the influence of physical forces on the regulation of bacterial behavior. This is important for future research approaches and could lead to new directions - for example, in the study of the swimming functions of naturally occurring E. coli strains, which are often pathogens, in their natural habitat, the human and animal gut."

![<p>Atomic crystal structure of activated [Fe]-hydrogenase</p>](/636742/teaser-1716364267.jpg?t=eyJ3aWR0aCI6MzYwLCJoZWlnaHQiOjI0MCwiZml0IjoiY3JvcCIsImZpbGVfZXh0ZW5zaW9uIjoianBnIiwib2JqX2lkIjo2MzY3NDJ9--4e67b9a3a27597158206bf7d411649c4c854ef47)

![<p>[Mn]-hydrogenase: A new step towards redesigning hydrogenases</p>](/584881/teaser-1560940570.jpg?t=eyJ3aWR0aCI6MzYwLCJoZWlnaHQiOjI0MCwiZml0IjoiY3JvcCIsImZpbGVfZXh0ZW5zaW9uIjoianBnIiwib2JqX2lkIjo1ODQ4ODF9--dc69e8f47e0c4c4922871284f94371c72e52b9c9)